|

.........

Suspect in Seal Beach nursing home killing charged with murder

88 year-old could get 50 year sentence

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

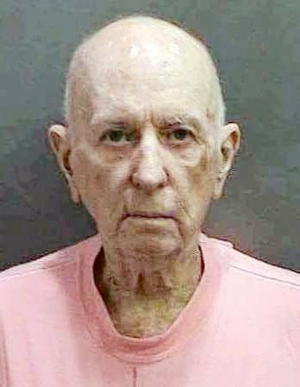

Roy Charles Laird, 88, is accused of fatally shooting

his 86-year-old wife, Clara, at a Southern California

nursing home Sunday. On Tuesday he was charged

with one felony count of murder, with a sentencing

enhancement for use of a firearm causing death. |

|

Suspect in Seal Beach nursing home killing charged with murder

Roy Charles Laird, 88, could be sentenced to 50 years in the shooting death of his wife of nearly 70 years, Clara, 86. The case shines a spotlight on the growing public debate about the appropriate response to such tragedies.

by Tony Barboza and Alan Zarembo

Los Angeles Times

November 24, 2010

When 88-year-old Roy Charles Laird was arrested Sunday on suspicion of killing his 86-year-old wife, Clara, at her nursing home in Seal Beach, the assumption was that he was trying to end her misery.

The couple's daughter called the single gunshot wound to the head a "mercy killing."

But on Tuesday, prosecutors had another word for it: murder.

The Orange County district attorney's office Tuesday charged Laird with one felony count of murder and a sentencing enhancement for the fatal use of a firearm. The offense carries a maximum sentence of 50 years in prison — the rest of his life if he's convicted.

The charges are expected to heighten a growing public debate about what punishment — if any — Laird and others in his position should receive. His supporters insist that Laird did the right thing, noting that his wife of nearly 70 years had long been suffering and recently lost the ability to feed herself, walk or sit up in a wheelchair. |

|

The case is a prime example of how society's values can clash with legal imperatives. "The problem is that what we think of as mercy killing is one of the clearest possible instances of premeditated murder," said Robert Weisberg, a professor of criminal law at Stanford University.

Prosecutors said the decision to charge Laird with murder was based on the legally relevant facts of the case, so the age of the suspect and the health of the victim did not factor in.

"There's no legal defense for a so-called mercy killing," said Orange County Dist. Atty. Chief of Staff Susan Kang Schroeder. "Mrs. Laird, no matter what mental state or physical state she may have been in, deserves protection by the people."

Laird is scheduled to answer the charges next week. His supporters argue that he had dedicated his life to Clara and was increasingly despondent about her deteriorating health. "Her mind was gone," the couple's 68-year-old daughter Kathy Palmateer told The Times on Sunday.

Prosecutors enjoy wide discretion over how to bring suspects like Laird to justice and sometimes decide to charge them with manslaughter or decline to file charges at all, said Yale Kamisar, a professor at the University of San Diego School of Law who has studied euthanasia and assisted suicide since the 1950s.

"Our society is really torn because there are arguments on both sides: There is a concern that you have to treat all life equally, and there's also a concern that you have to show compassion; so you're never sure how it's going to come out," he said.

This case, he said, could hinge on how united the family is behind Laird's decision to take his wife's life.

"These are not things that are in the statute books, but those are the kinds of factors that in past cases have made a difference," Kamisar said.

Weisberg said that in such cases prosecutors often initially file murder charges, only to later scale them back to lesser offenses and negotiate pleas in exchange for light punishments.

"They recognize the absurdity of bringing this to the conclusion of a full murder sentence," he said. "But they can't simply exonerate the guy."

The danger is that other people in similar circumstances might be encouraged to do the same thing. And from a legal perspective, it would be difficult to justify why some killings are acceptable and others are not.

"There's a bit of kabuki theater with these cases," Weisberg said. "But most people seem to be satisfied that those contrivances are the right thing to do."

The killing at the Country Villa Healthcare Center in Seal Beach drew comparisons to a similar killing last fall at Laguna Woods Village, a retirement community at the other end of Orange County. In that case, manslaughter charges were dismissed soon after they were filed because the suspect died.

Prosecutors said that retired medical doctor James Fish, 90, of Laguna Woods gave his terminally ill 88-year-old wife morphine to ease her pain before killing her with a gunshot wound to the head. He then shot and wounded himself but initially survived, garnering sympathy from others within the walled-in retirement village.

The day after the killing, the Orange County district attorney's office charged Fish with voluntary manslaughter in the death of his wife of 50 years and a sentencing enhancement for using a firearm.

Fish died of his injuries two weeks later, so charges were dropped.

Even when mercy killers are convicted, they sometimes receive leniency at the time of sentencing. In 2000, a Ventura County judge ordered a 67-year-old Thousand Oaks man to serve only two years' probation for fatally shooting his seriously ill wife, calling it a tragic case that warranted compassion.

Although such cases often generate strong public sympathy for the suspects, some experts said that understanding the motivations can be complex.

Donna Cohen, a professor of aging and mental health at the University of South Florida in Tampa, said that such cases have more to do with depression than mercy.

"Family members like to believe it was done out of love," she said. "But it was done out of depression.

"These men don't have a desire to kill their wives," she said. "It's motivated by sincere depression, a sense of not being able to do anything else, a real sense that there is no way out."

Typically, such killings are followed by the perpetrators' suicides. Cohen's research shows that usually the female victims are not aware of their husbands' plans. The men often have a strong sense of responsibility to their families.

With its large population of elderly residents, Florida sees one such case every couple of weeks, she said.

Cohen estimated that there are about 10 cases a year nationwide in which the husband does not take his own life as well.

She said many such deaths can be prevented by looking for warning signs. Chief among them: a husband who spends most of his time at the nursing home, as was the case with the Lairds.

"This was a time bomb waiting to happen," Cohen said. |

|

|

|

|